Iceland's passion for family trees

- Patrick

- Nov 16, 2021

- 5 min read

Genetic research into one's origins has yielded unexpected dividends in the fight against the Corona Crisis

An evening on Laugavegur, the party mile of Iceland's capital Reykjavik. Two young people have just met in one of the many bars. They are having a great time and the evening is developing promisingly. As it becomes increasingly clear that their plans could extend beyond curfew, they pull out their smartphones and briefly tap them together. A brief moment of tension follows.

Iceland is a country with a small population: the island has just 368 000 inhabitants. For centuries, people lived in isolation, and the Icelandic gene pool rarely received impulses from outside. Actually, everyone is somehow related to each other. And you want to be sure that the nice person you just met is not too closely related. That's exactly what the app that the two of them use clarifies. They are lucky - they are not close relatives.

The Power of Genealogy

The scene described is fictitious, but it could well have happened that way. For the app does indeed exist. But to find out how and why it came about, a bit of back story is necessary, combined with a visit to a modern building complex on the outskirts of Reykjavik's university district. There, in a large office behind a sprawling desk full of books, equipment and papers, sits Kari Stefansson, the founder and CEO of Decode Genetics. Stefansson is a professor of neurology and taught for many years at prominent universities in the USA. Since 1996, however, his passion has been the question of who Icelanders actually are. And for him, the way to the answer is through genealogy and genetics.

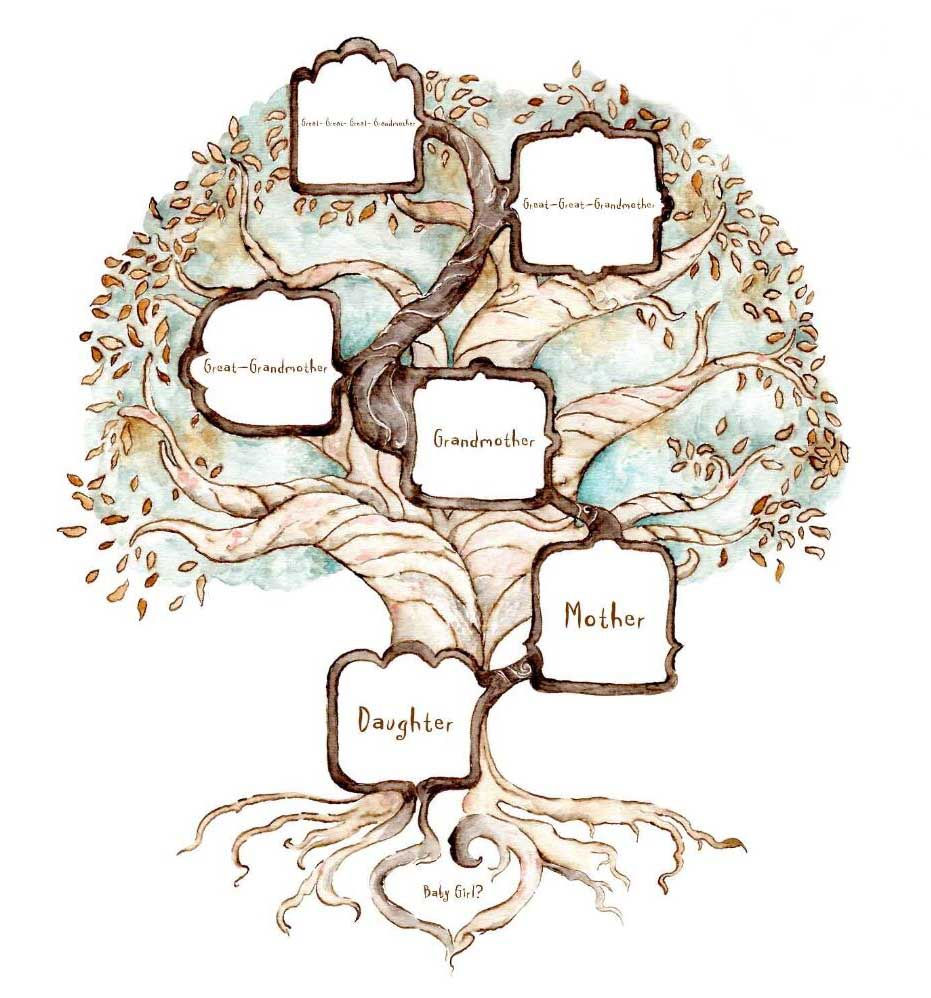

"The Icelandic sagas," says Stefansson, "were about the daily life of the people of that time, the common people. And they always began with family history." Genealogy, he says, is important for one's identity. That's why his company has taken on the task of building a digital genealogical database. To this end, many different sources were tapped, public and private, from censuses, population registers and church records to family histories and privately compiled family trees.

The result was Islendingabok, the "Book of Icelanders", an internet-based database. Today, anyone with an Icelandic national insurance number has access to it. The database soon proved to be extremely popular - no wonder when family history can be traced back over centuries. And that is why something special was thought of for the tenth anniversary of the launch of the "Book of Icelanders": A competition was announced for an app that would make the database accessible from a smartphone.

The trio of programmers who won the competition came up with a special feature: If two people want information about their degree of relationship, then instead of entering names into the database, they can simply tap their smartphones briefly against each other. In this electronic tête-à-tête, the relevant information about the owners of the national insurance numbers is exchanged, and if there is no kinship obstacle in the way of getting closer to each other, the screen cheerfully announces: "Go ahead!"

It didn't take long for the word about this curious "anti-incest app" to go around the world. A tongue-in-cheek Youtube spot helped a lot. From tech magazines to global mainstream media: everyone reported. But is the app actually used in real life, or was it mainly a gag? We hear very different things about it. Some claim to swear by it when dating. Others say the app was conceived more as a joke and has now simply developed a life of its own as a funny story with its worldwide resonance.

Contribution to research

What is undisputed, however, is the popularity of the database on which the app is based. It now consists not only of digitised written sources, but also biomedical information. For at the same time as compiling the historical sources, Decode Genetics also collected blood samples that Icelandic citizens voluntarily gave for the purpose of genetic analysis. In the meantime, samples from about half of the population are stored in a deep-freeze warehouse in the basement.

And there is more at stake than just family trees. A comprehensive genetic analysis reveals laws and mechanisms and thus allows conclusions that could be important for public health, says Kari Stefansson. Being able to determine a patient's individual risk profile for hereditary diseases is important if the health care system is to focus more on prevention. To understand oneself, including biologically, it is important to study human diversity in the broadest sense, Stefansson says. And if you want to classify something as "pathological", you first have to be able to define what is "normal". The fact that so many Icelanders are willing to participate here is an extraordinary contribution to this research.

But what about concerns about data security? Genetic information is extremely personal and sensitive. Here Stefansson expands a little further, and his voice mingles with a hint of discomfort. Society, he says, regards the right to a state-of-the-art health care system as a human right. But this entitlement is also accompanied by the obligation to make research possible. This is often forgotten. Sometimes he has the impression that modern society has come to value the safety of patient data more than the safety of the patients themselves, says Stefansson.

Not that Stefansson disregards the aspect of data security. The protection of information is eminently important, and that is why data is anonymised in biomedical research. This is at the other end of the scale from the security consciousness of those people who use their smartphones and their social media presence to make their entire lives public.

Hand in hand against Covid

If Stefansson counts on the public's help for the work of his company's genetic research, he is also prepared to give something back to the community. When the Corona crisis broke out almost two years ago, the company got involved right from the start and offered its laboratories to the public health system for Corona testing and analysis of the virus variants. The genetic material of the virus was examined for every single case of covid diagnosed, says Stefansson. Therefore, they had a very good picture of where which variant had been introduced from and how it had circulated in society. This enabled the authorities to respond with precision.

In fact, Iceland has come through the crisis enviably well. Decode Genetics, a private company under the umbrella of the biotech corporation Amgen, worked hand in hand with the public actors. "It was an 'all hands on deck' situation," says Stefansson, "and it was gratifying to see how the generally rebellious Icelandic society was able to unite under the threat." For him, he concludes, the pandemic was therefore not all negative.

Source:

Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 16.11.2021, article by Rudolf Hermann, Reykjavik / free translation

Comments